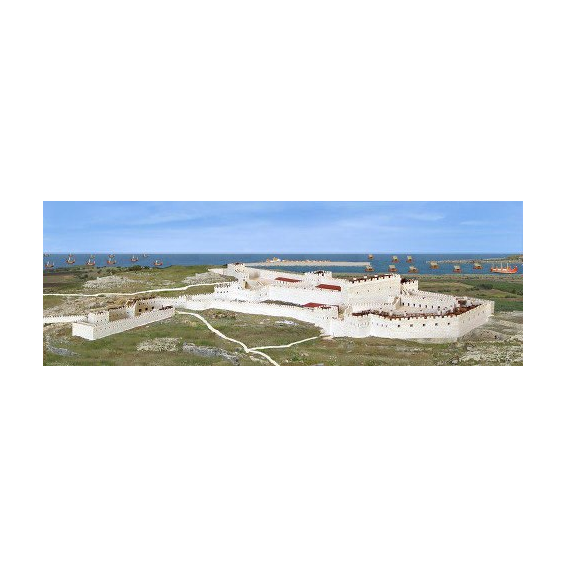

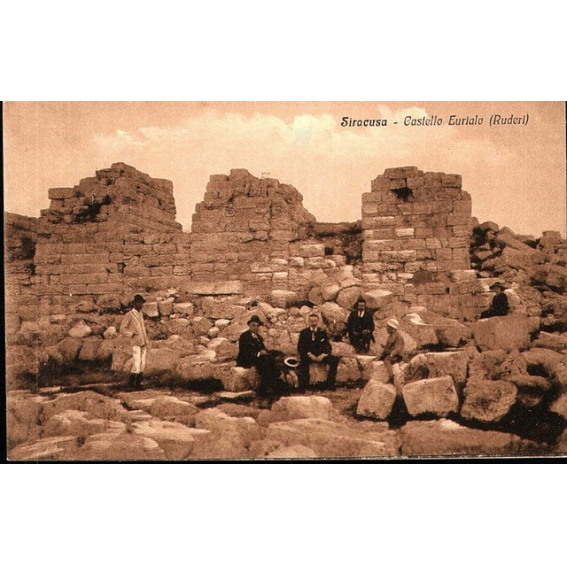

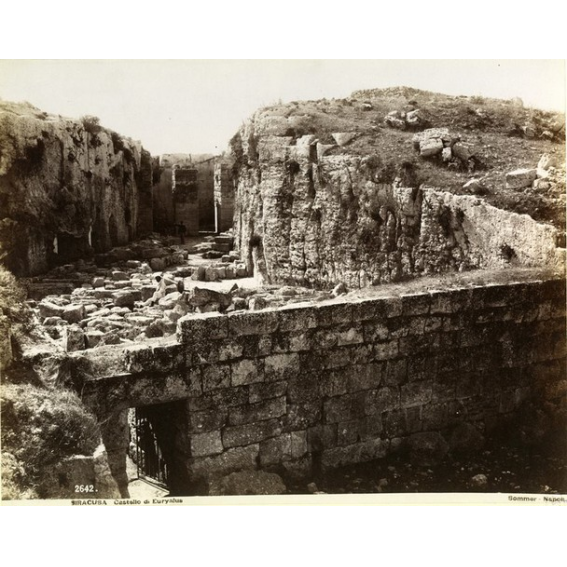

Castello Eurialo

Il castello Eurialo e le mura di Dionigi

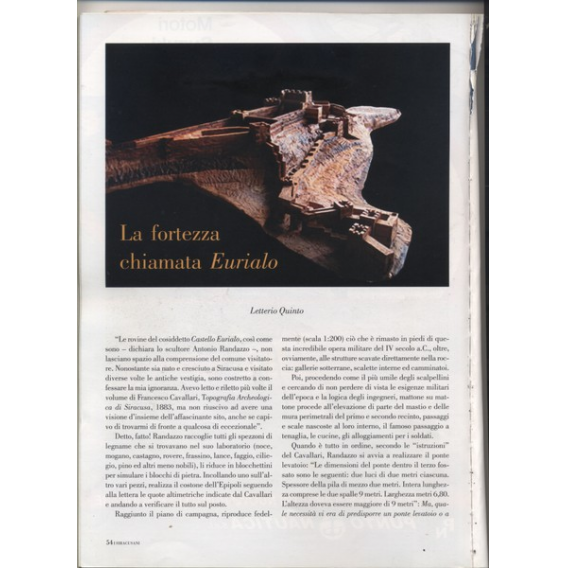

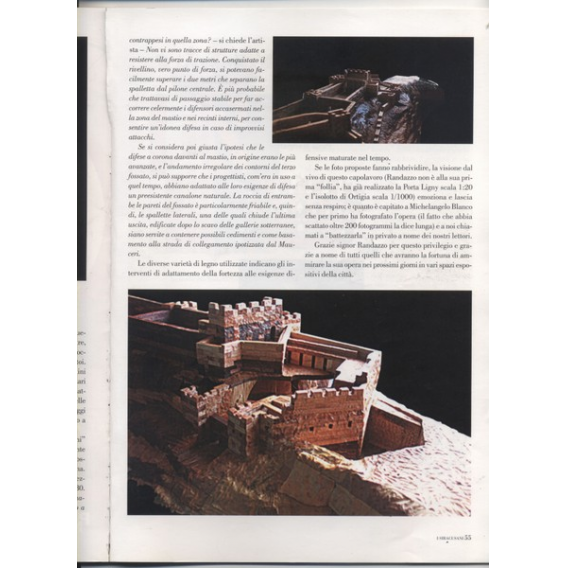

documentazione PDF di Antonio Randazzo

interessante anche questa documentazione a proposito delle armi antiche

L’arte dell’assedio e della difesa nella Grecia antica. Teorie fonti e fortificazioni fra VI e III sec. a.C.

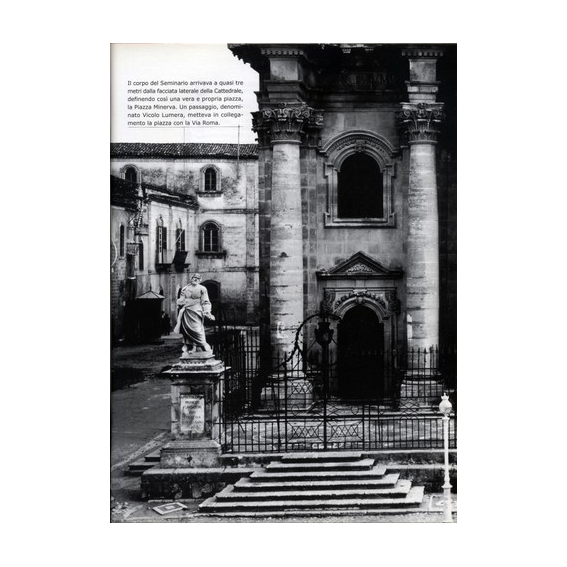

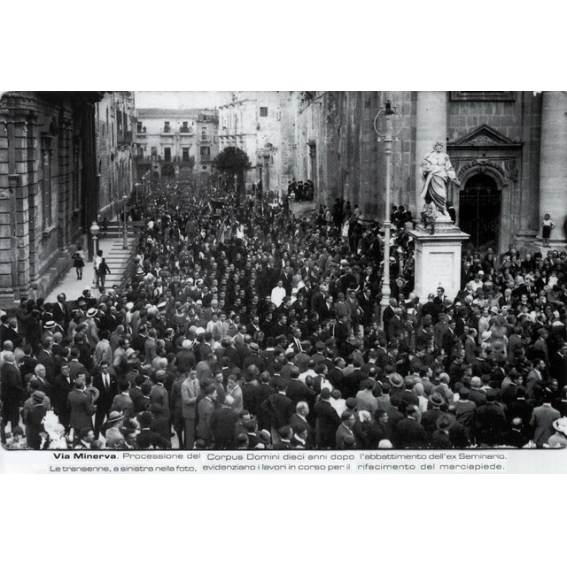

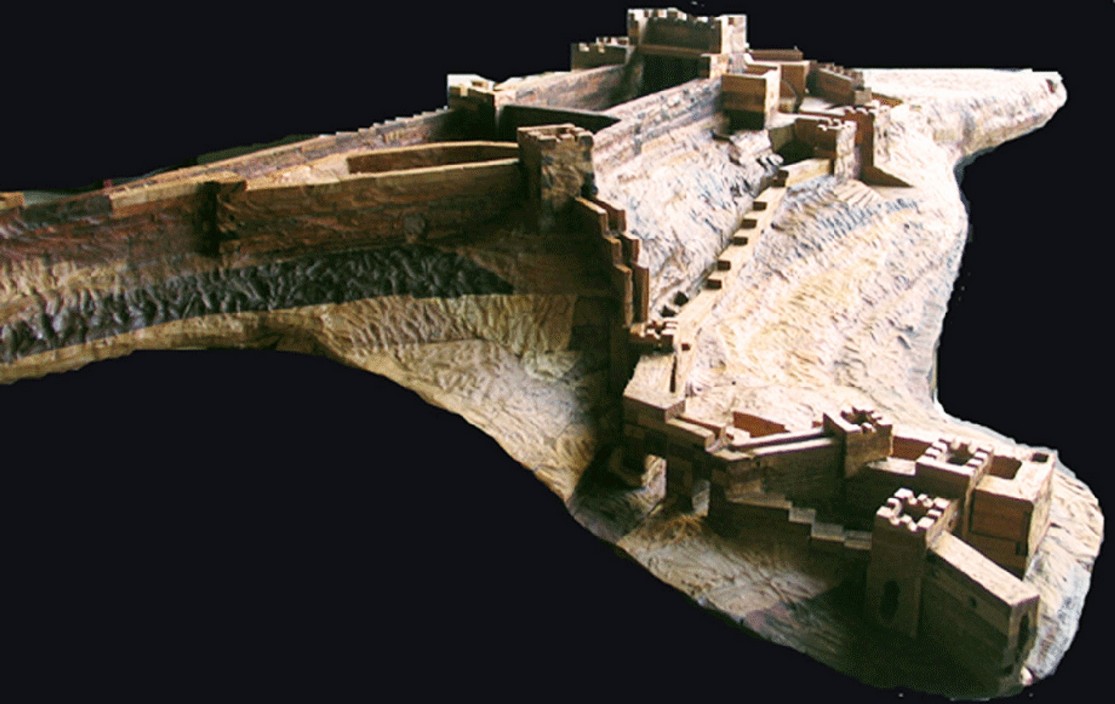

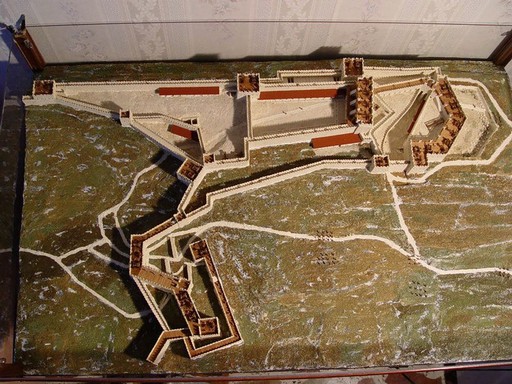

la mia scultura

riproduzione di Bosco Nunzio

tratto da galleria Roma Siracusa

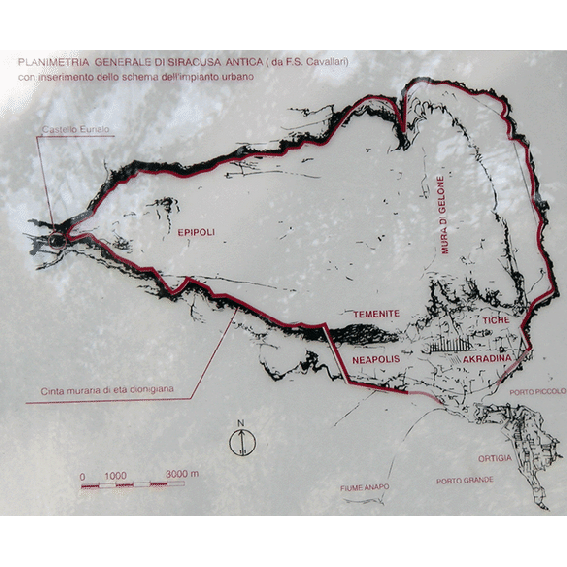

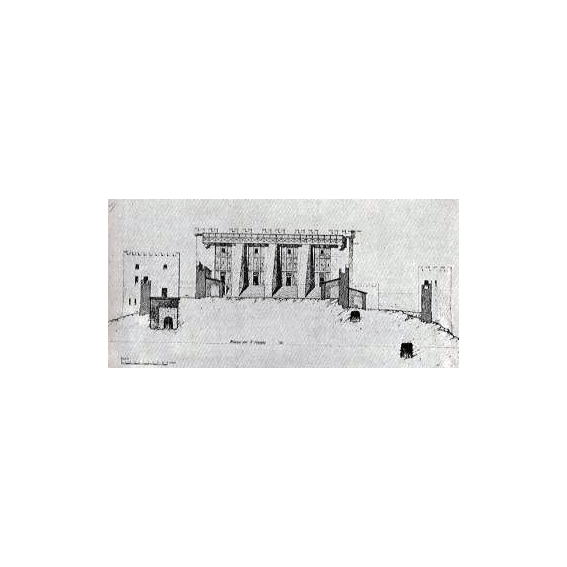

« Avendo visto che durante la guerra con Atene la città era stata bloccata da un muro che andava da mare a mare, temeva, in casi analoghi, di venir tagliato fuori da ogni comunicazione con il territorio circostante: vedeva bene, infatti, che la località chiamata Epipole dominava la città di Siracusa. Rivoltosi ai suoi architetti, in base al loro consiglio decise di fortificare le Epipole con un muro, ancora oggi conservato nella zona intorno all'Exapylon (le " sei porte "). Questo luogo, rivolto a Settentrione, interamente roccioso e a picco, è inaccessibile dall'esterno. Desiderando che le mura fossero costruite con rapidità, fece venire i contadini dalla campagna, tra i quali scelse gli uomini migliori, in numero di 60.000, e li distribuì lungo il settore di muro da costruire. Per ogni stadio designò un architetto e per ogni pietre un mastro muratore, a ciascuno dei quali assegnò 200 operai. 6.000 gioghi di buoi erano impiegati nel luogo designato. L'attività di tanti uomini, che si applicavano con zelo al loro compito, presentava uno spettacolo straordinario. E Dionigi, per stimolare l'entusiasmo di questa moltitudine, prometteva grandi premi a coloro che avessero: terminato per primi, specialmente agli architetti, poi anche ai mastri muratori, infine agli operai. Egli stesso, con i suoi amici, assisteva ai lavori per intere giornate, ispezionando ogni luogo e facendo sostituire quelli che erano stanchi. In breve, rinunciando alla dignità del suo ufficio, si riduceva a un rango privato, e assoggettandosi ai lavori più pesanti, sopportava la stessa fatica degli altri: ne nacque di conseguenza una grande emulazione, e alcuni aggiungevano .anche parte della notte alla giornata lavorativa. Tale era l'entusiasmo di quella massa di lavoratori. Di conseguenza, il muro fu terminato, al di là di ogni speranza, in 20 giorni: esso era lungo 30 stadi, e di altezza proporzionata, e così robusto da esser considerato imprendibile. Vi erano alte torri a intervalli frequenti, costruite con blocchi lunghi 4 piedi, accuratamente giuntati ».

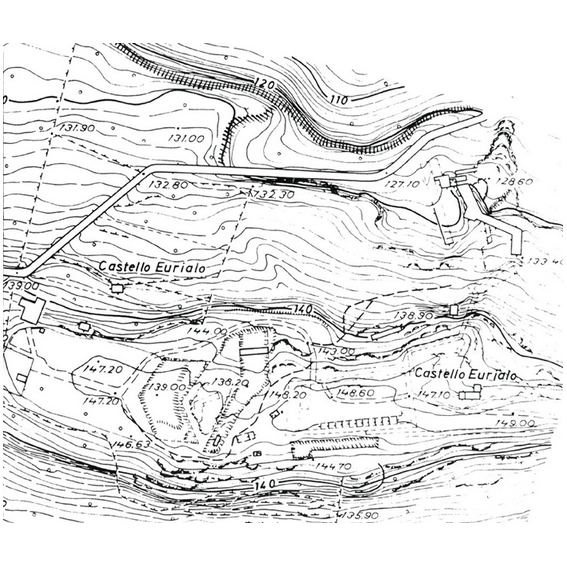

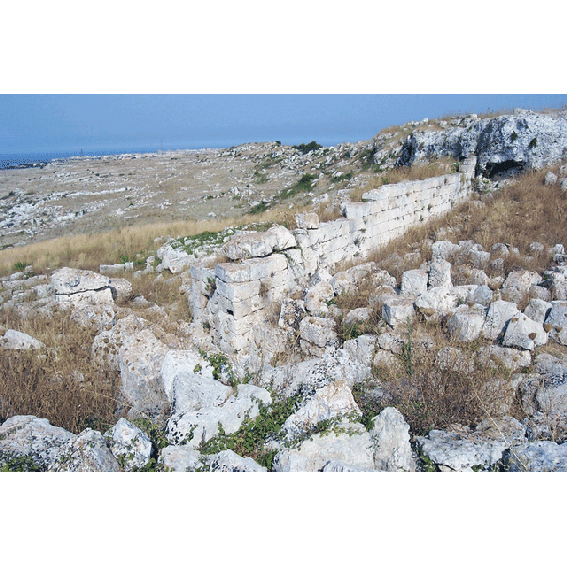

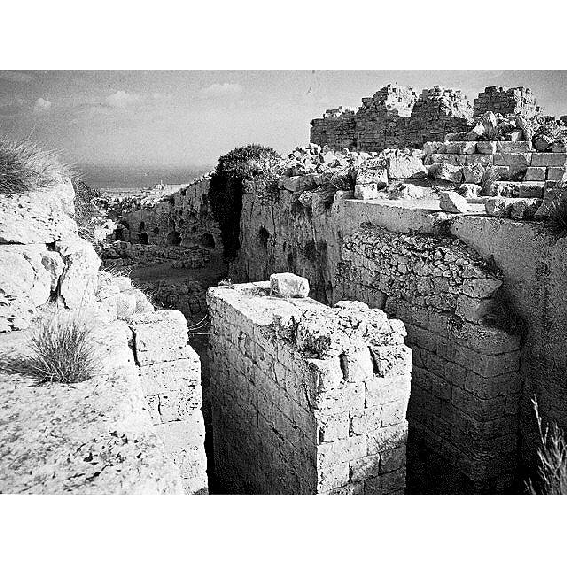

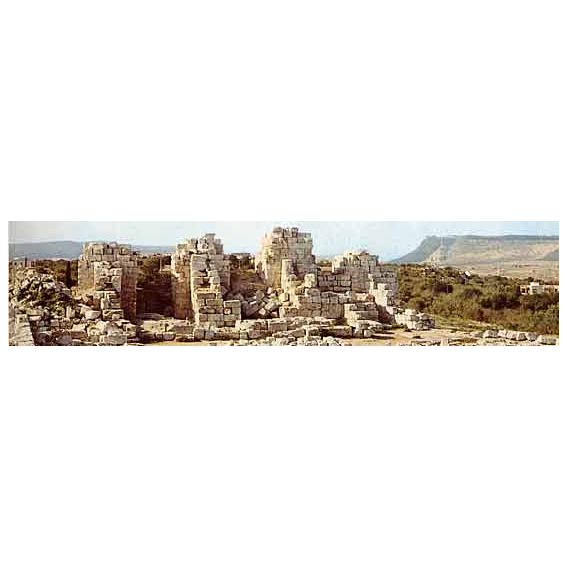

Questi lavori riguardano evidentemente solo la parte nord delle Epipole, il lato cioè più sguarnito, e che era più urgente fortificare: la lunghezza di questo muro, 30 stadi (probabilmente stadi attici di 177,6 m), corrisponde a circa 5528 m. Si tratta di una indicazione notevolmente precisa, poiché la lunghezza delle mura dionigiane nel settore nord, tra il mare e il Castello Eurialo, è di circa 5580 m (Dionigi fornisce evidentemente una cifra tonda). Una conferma della descrizione antica si ricava anche dalla tecnica di costruzione del muro, che è assolutamente omogenea nel settore nord (segno evidente di unità di esecuzione), mentre presenta differenze notevoli negli altri settori, che sembrano realizzati in tempi più lunghi, e con maestranze diverse.

I lavori dovettero proseguire negli anni successivi nei settori sud ed est, e furono terminati probabilmente, intorno al 585, poiché Diodoro ne parla in corrispondenza di quell'anno, affermando che la cinta era ormai conclusa, e che era la più ampia esistente in una città greca (XV 15, 5). Le misure ci sono fornite da Strabone (VI 2, 4), per il quale tutta la cerchia di mura misurava 180 stadi, cioè, in stadi attici, poco meno di 52 km. Anche se si tratta ancora una volta di una cifra arrotondata, essa corrisponde con buona approssimazione alla realtà (circa 51 km). Che il settore meridionale non fosse del tutto terminato nel 596 risulta chiaramente da un episodio di quell'anno, quando Imilcione occupò il quartiere esterno dell'Acradina (più o meno corrispondente alla zona del Fusco), e saccheggiò il santuario di Demetra e Kore. Questa zona, particolarmente vulnerabile, fu in seguito protetta da una grandiosa fortificazione, che si staccava dalla portella del Fusco in direzione sud, inglobando gran parte della necropoli. Settori di un grandioso muro, spesso 6 m, furono scavati alla fine del secolo scorso nei pressi del cimitero, ma è probabile che la muraglia in questo settore fosse addirittura doppia. Essa doveva poi continuare lungo il margine della terrazza del Fusco, fino a collegarsi con un altro tratto di muro, visto a nord del cosiddetto ginnasio, e poi con le mura di Acradina.

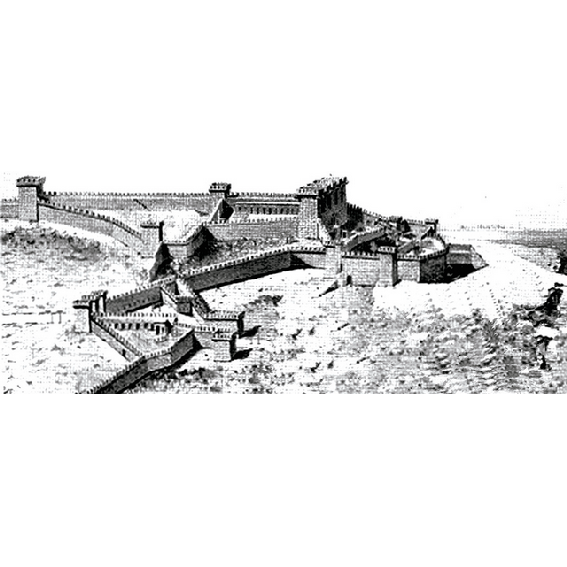

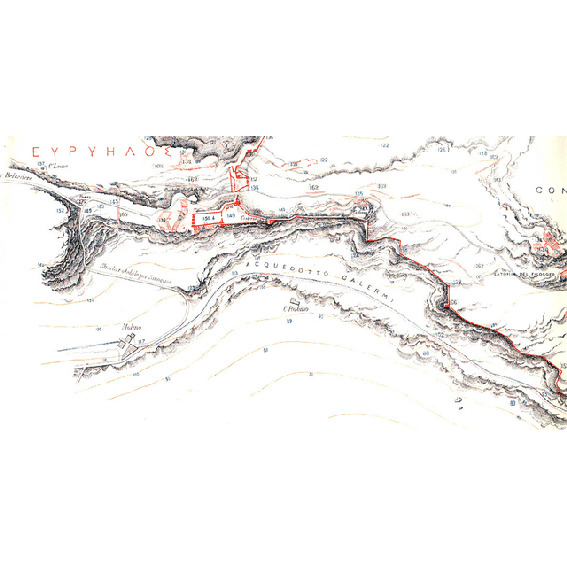

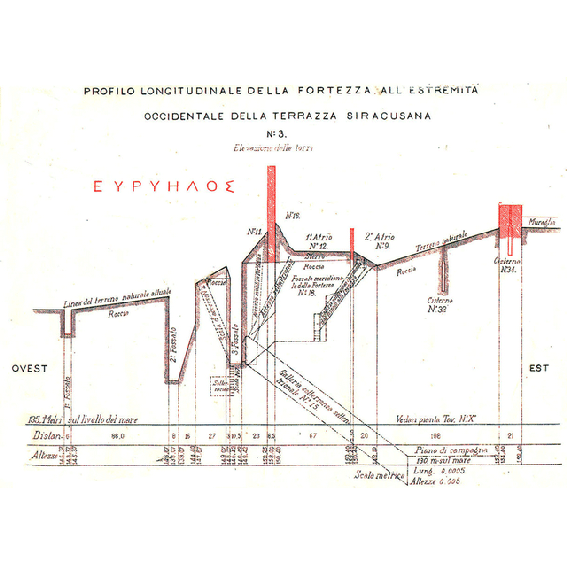

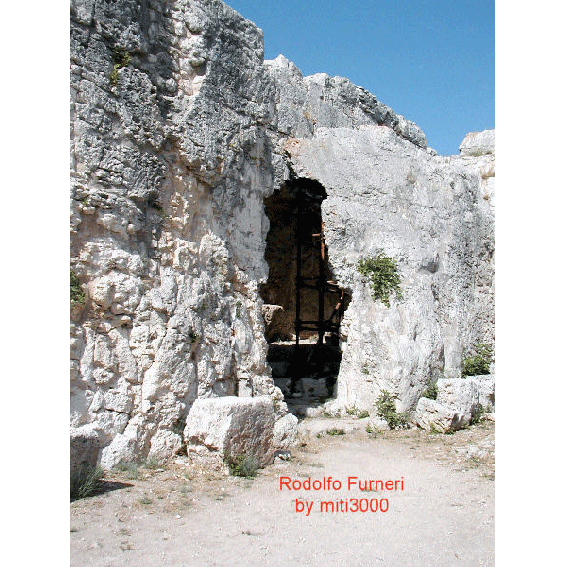

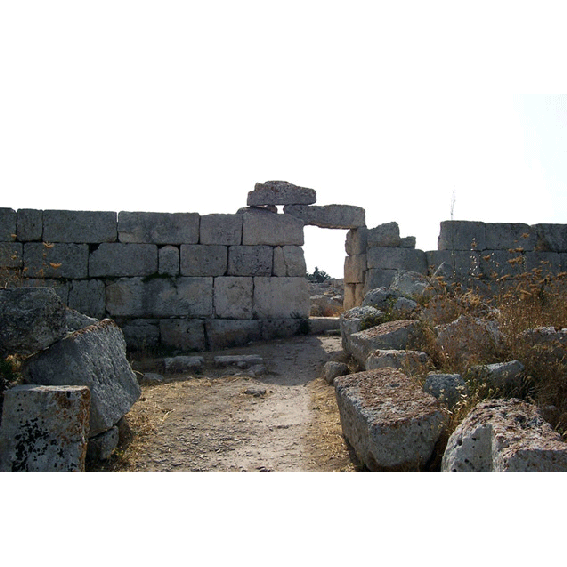

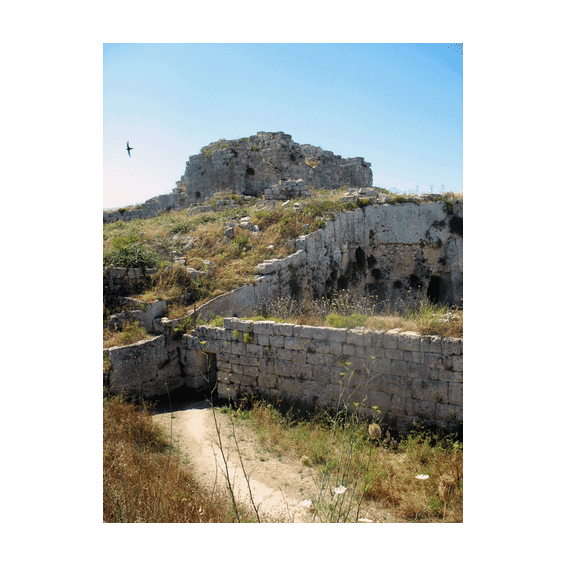

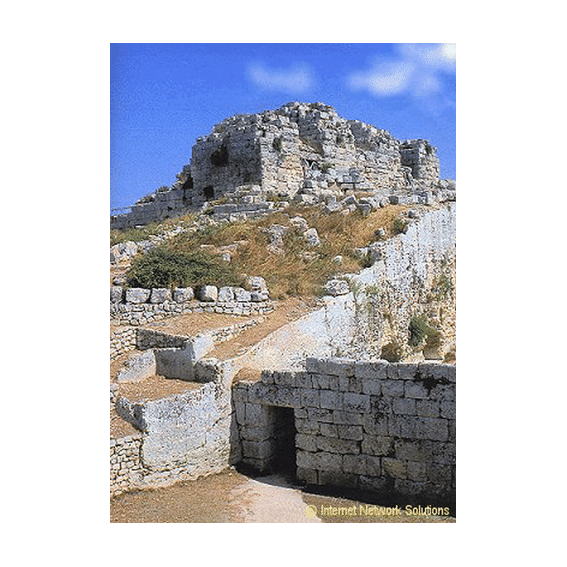

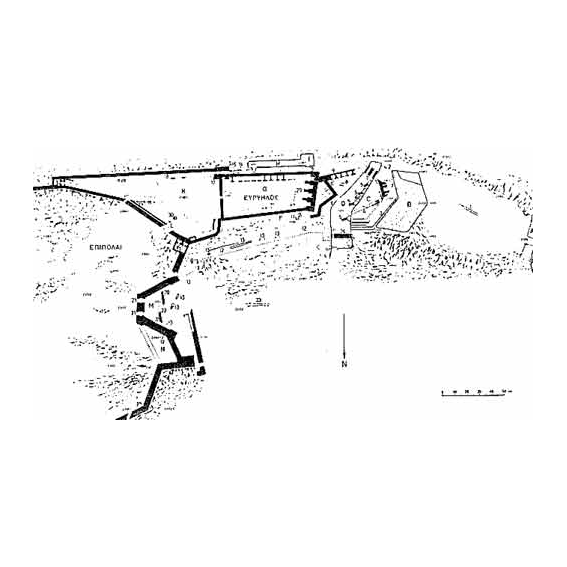

Il punto più delicato delle Epipole era il loro vertice occidentale, dove il grande pianoro si stringe fìno a formare uno stretto istmo, punto naturale di accesso della terrazza alle spalle di Siracusa. Il nome che veniva dato a questa località, Euryalos, significa forse « largo chiodo », e sembra riferirsi alla forma dell'istmo. Lo troviamo già menzionato a proposito dell'assedio ateniese: da qui infatti gli Ateniesi entrarono due volte sulle Epipole; al momento del primo assalto contro Siracusa, e poi dopo la rioccupazione delle Epipole da parte dei Siracusani, quando Demostene cercò " di riprenderle al nemico (Tucidide, VI 97, 2; VII 43, 3). Anche Gilippo, giunto in soccorso della città, vi entrò dall'Eurialo: segno che questo era il principale accesso per chi provenisse dall'interno dell'isola (Tucidide, VII 2, 4). I Siracusani se ne rendevano ben conto, e lo avevano fortificato già nel corso della guerra contro gli Ateniesi. Fu tuttavia Dionigi, probabilmente, a costruire il primo forte stabile, che assunse lo stesso nome della località. Le sue dimensioni dovevano essere notevoli già nel IV secolo, se nel corso dell'assedio cartaginese del 309 i Siracusani poterono concentrarvi 3.000 fanti e 400 cavalieri (Diodoro, XX 29, 4), che riuscirono a respingere, proprio in grazia della ristrettezza del luogo, il grande esercito nemico. Anche nel corso dell'assedio romano Marcello, pur dopo aver occupato le Epipole, si rese conto che il castello era imprendibile (Livio, XXV 25, 2-5), e tentò di farselo consegnare dal comandante della guarnigione, l'argivo Filodemo. Esichio definisce il luogo come l'acropoli delle Epipole, e Livio ne parla come di un fumulus (collina isolata) o di un'arx (cittadella). È proprio Livio a fornircene la migliore descrizione antica: « Si tratta di una collina isolata nella parte estrema della città, nella direzione opposta al mare, che domina le vie che portano verso l'interno dell'isola, situata in modo particolarmente favorevole a ricevere i rifornimenti ».

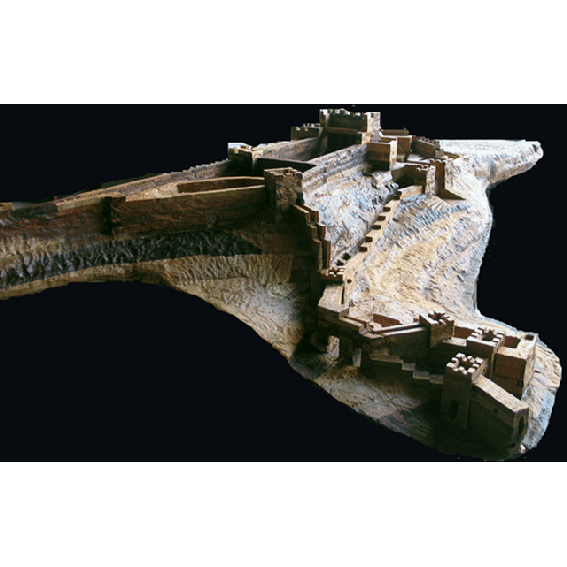

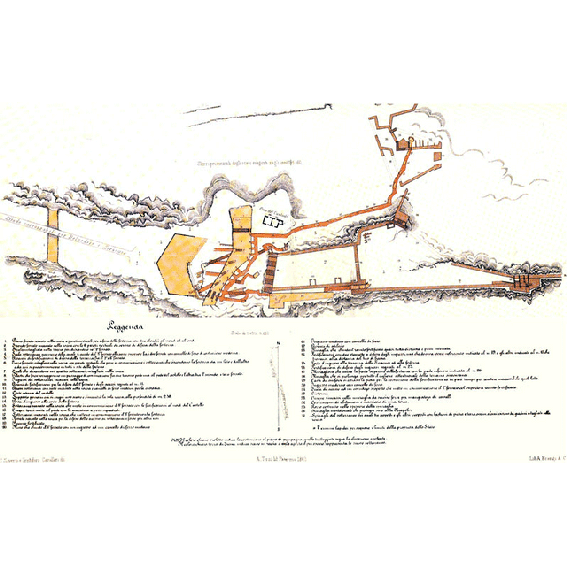

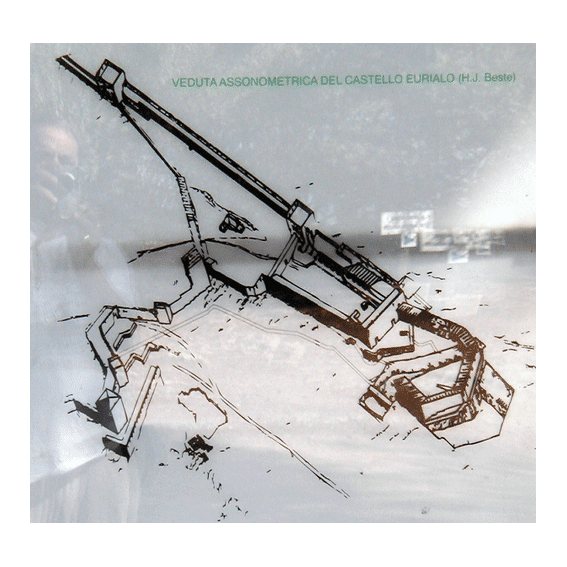

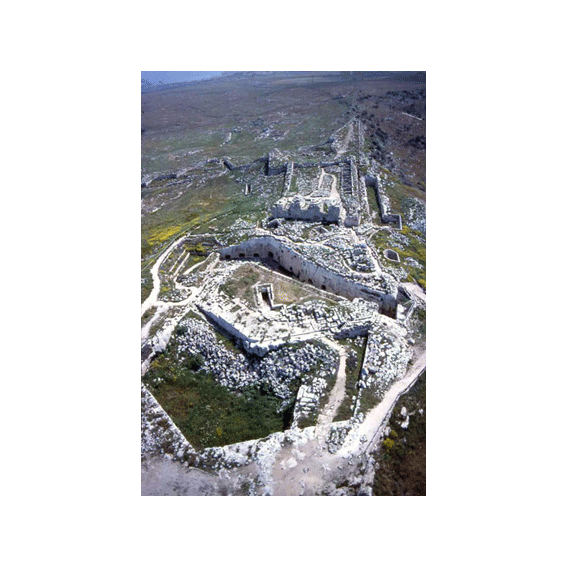

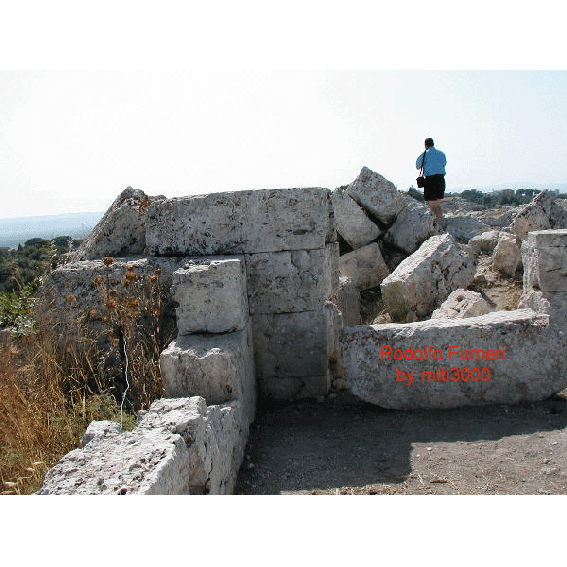

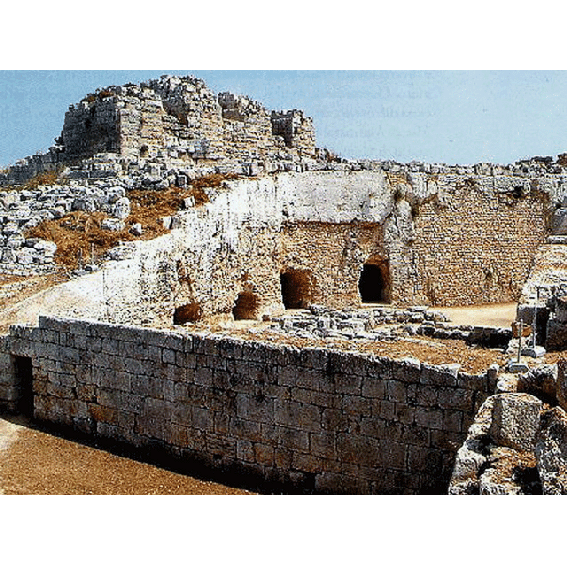

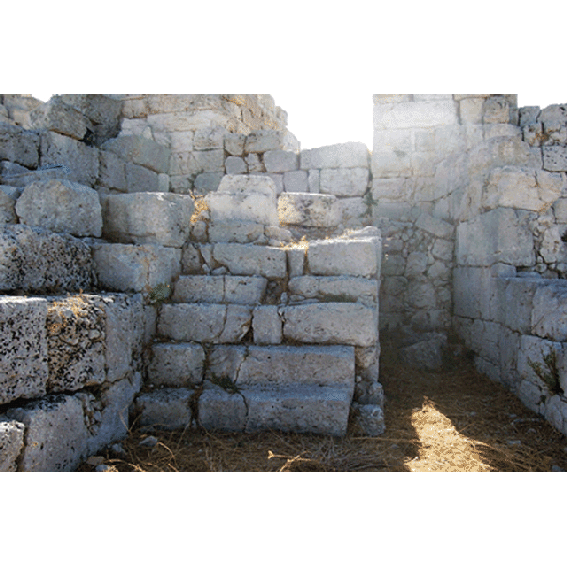

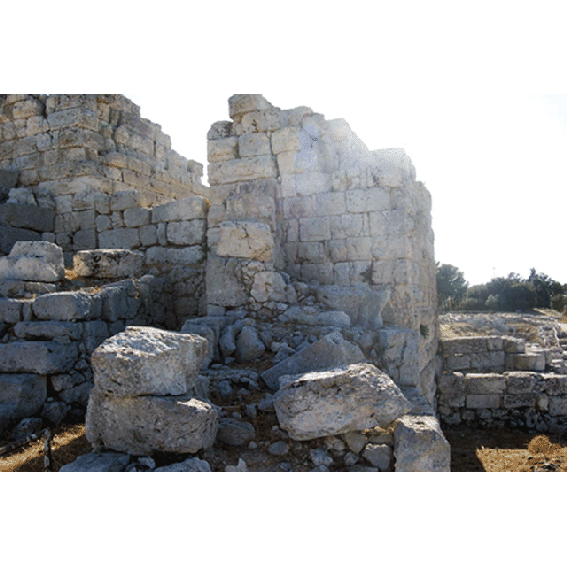

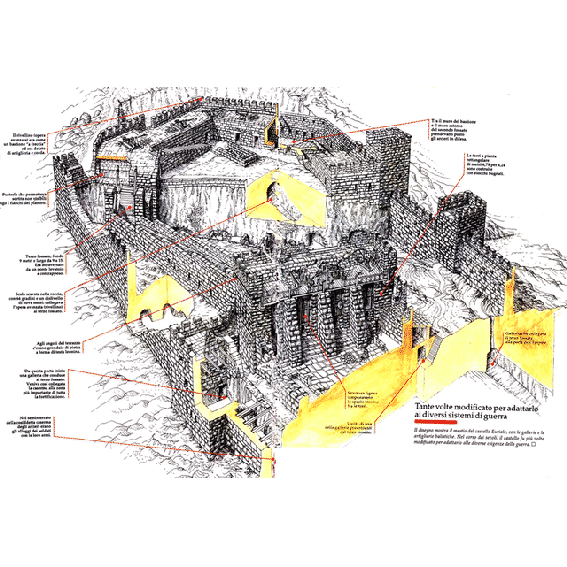

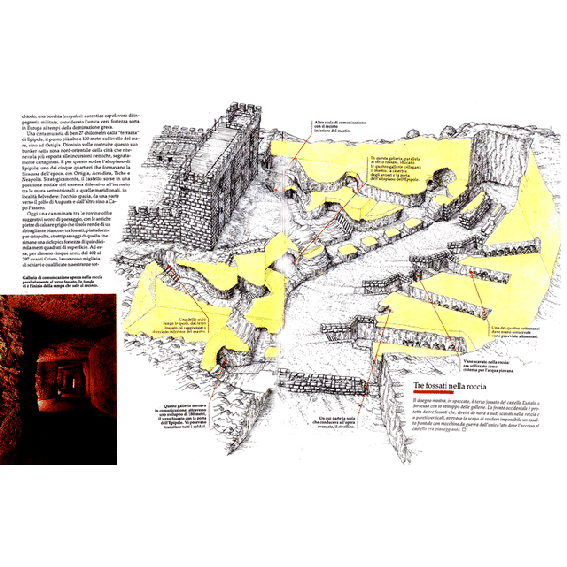

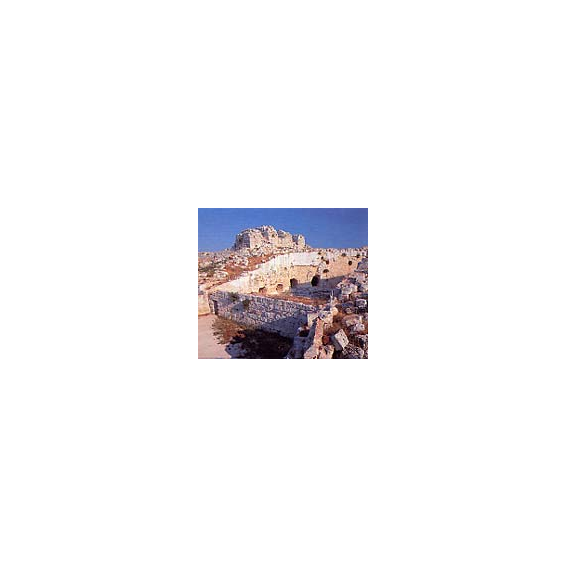

I resti attualmente visibili del castello solo in minima parte corrispondono all'originaria costruzione dionigiana: essi sono il risultato di successivi rifacimenti e perfezionamenti, che occupano il lungo periodo di tempo compreso tra la fine del v sec. a. C. e l'assedio romano di Marcello. È anzi probabile che la ristrutturazione definitiva (che non fu completata) appartenga proprio agli ultimi anni di questo periodo: essa si può attribuire a lerone II, il quale, come ricorda Plutarco, si servì ampiamente dei suggerimenti tecnici di Archimede (Plutarco, Vita di Marcello, 14, 8). È quanto mai probabile che le installazioni raffinatissime del castello, che ne fanno la più complessa opera difensiva che ci sia giunta del mondo greco, siano state progettate proprio da Archimede: esse corrispondono infatti allo stadio più avanzato della poliorcetica ellenistica, quale la conosciamo attraverso l'opera di un contemporaneo dello scienziato siracusano. Filone di Bisanzio. Dopo il lungo periodo di pace, corrispondente all'occupazione romana, il castello fu riattato in periodo bizantino, come mostrano alcune tarde strutture superstiti.

Il castello (che occupa una superfìcie di circa 15.000 m2), è preceduto da un piccolo Antiquarium, adattato nella casa del custode, dove sono conservati i più importanti materiali trovati nel corso dei vari scavi, realizzati a partire dal secolo scorso. Vi sono esposti: due gocciolatoi a testa leonina, provenienti dalle torri del mastio centrale, databili ancora entro il IV sec. a. C., e quindi appartenenti a una delle più antiche fasi della fortificazione; un rilievo in cui forse è rappresentata una catapulta (macchina da guerra che fu inventata dagli ingegneri di Dionigi il Vecchio); frammenti di una grande iscrizione greca, trovati davanti alla porta con opera a tenaglia a nord del castello: vi si legge in parte il termine basileus (« rè »), ciò che dimostra un intervento piuttosto tardo, da attribuire ad Agatocle o a lerone II (più probabilmente a quest'ultimo), poiché fu proprio Agatocle il primo dinasta di Siracusa ad assumere il titolo regio.

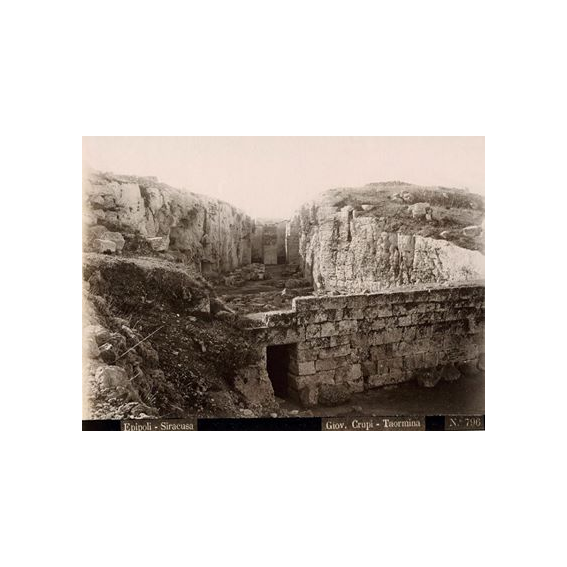

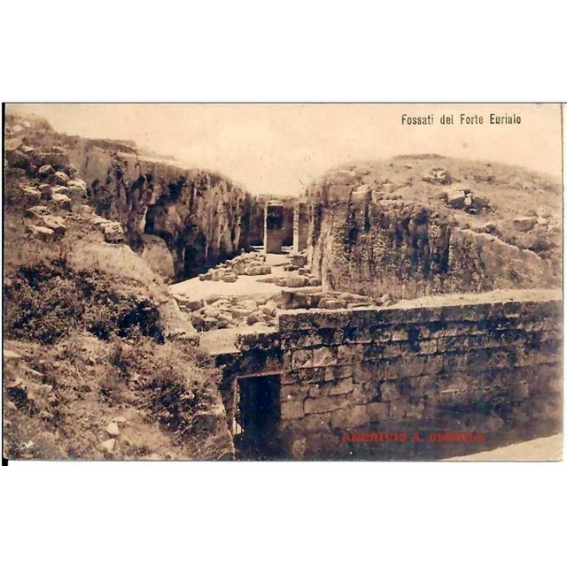

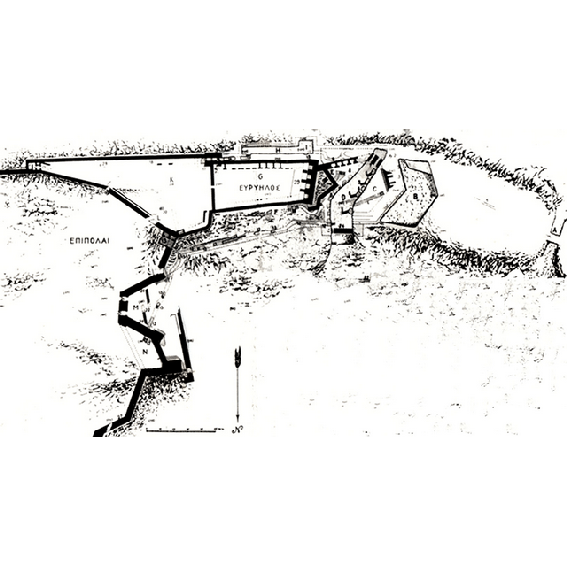

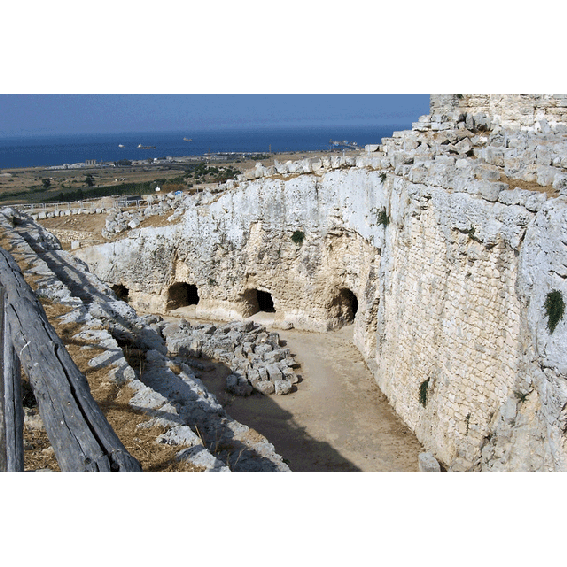

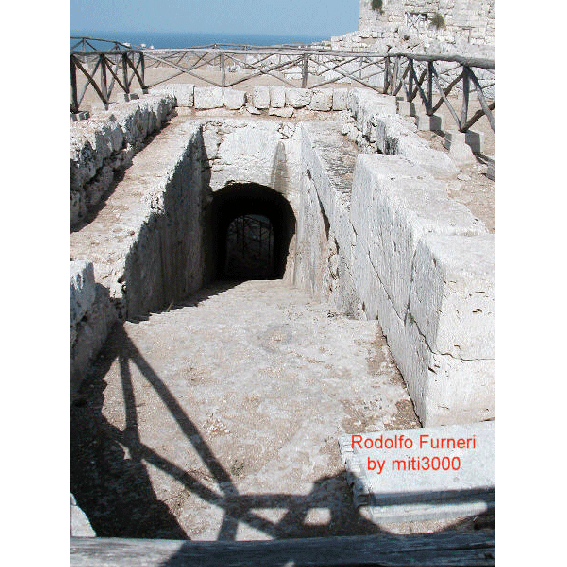

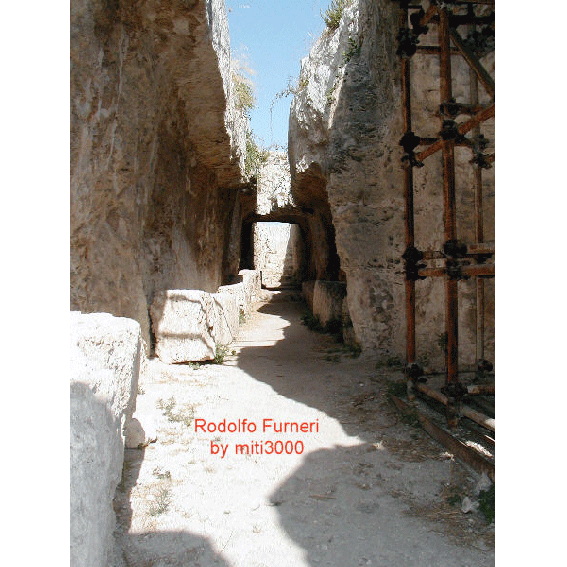

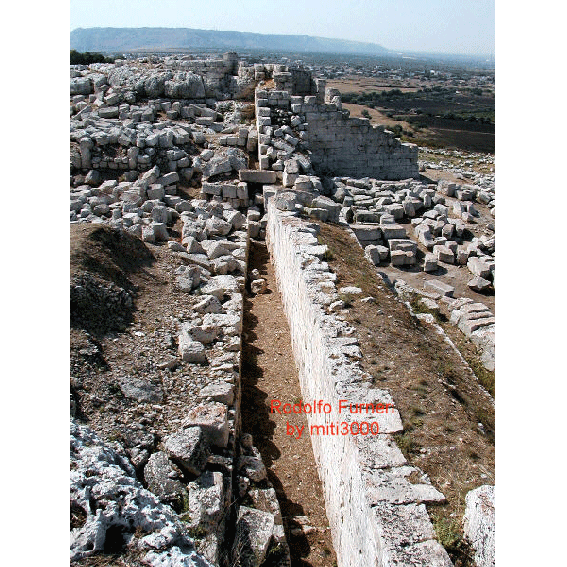

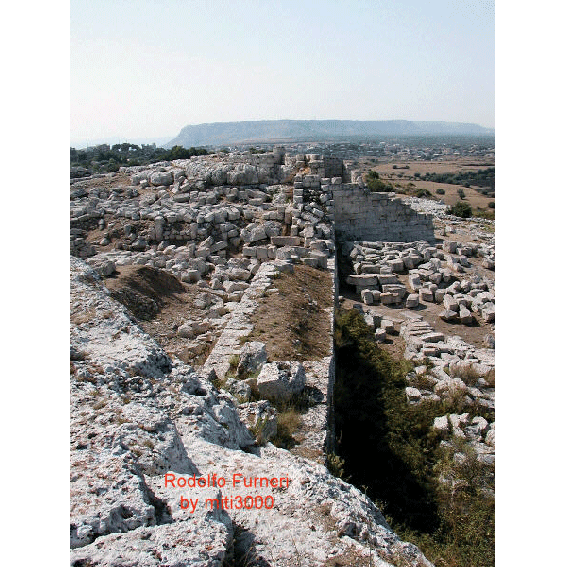

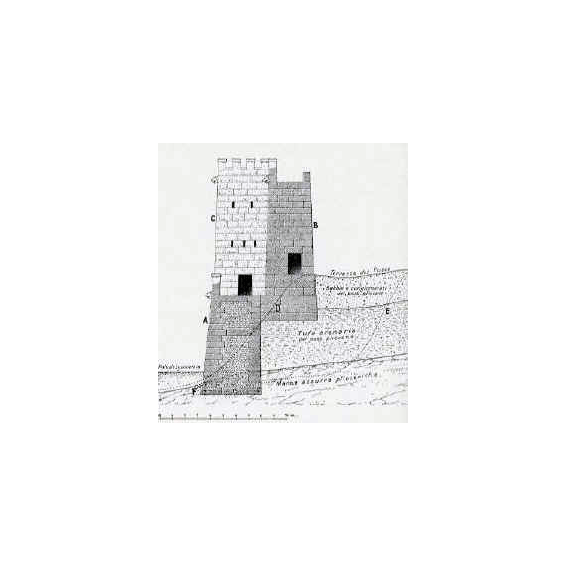

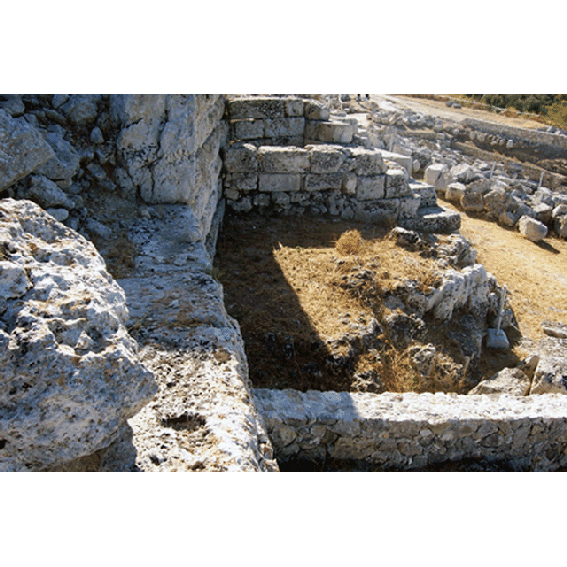

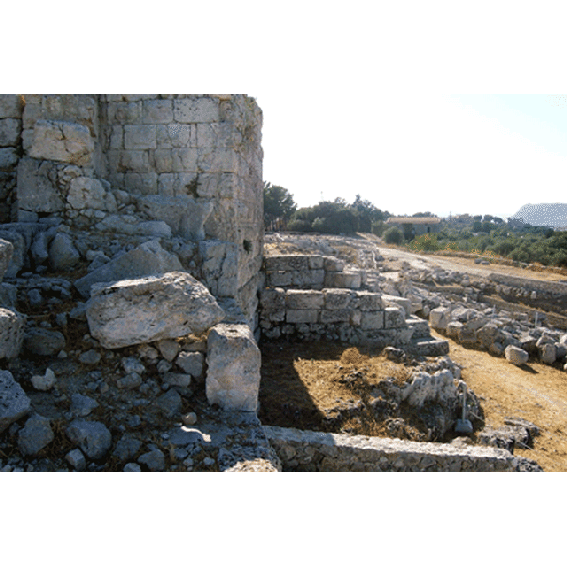

Le strutture del forte erano precedute da tre fossati successivi. Il primo di questi (A), che non fu mai terminato, è proprio accanto all'Antiquario, ed è lungo 6 m e profondo 4. È stato notato che esso si trova a circa 566 piedi (182 m) dalla fronte del mastio: ciò corrisponde abbastanza bene alle norme di Filone di Bisanzio, il quale afferma che una fortificazione deve essere difesa da non meno di tre fossati, e che il più lontano di questi deve trovarsi a non meno di 535 piedi^in modo da mettere la fortificazione stessa fuori della portata delle balliste più potenti. La maggiore distanza, in questo caso, si spiega con il fatto che le balliste del castello erano collocate su torri a una certa altezza, e la loro portata era di conseguenza maggiore di quella possibile per gli attaccanti, che si trovavano molto più in basso.

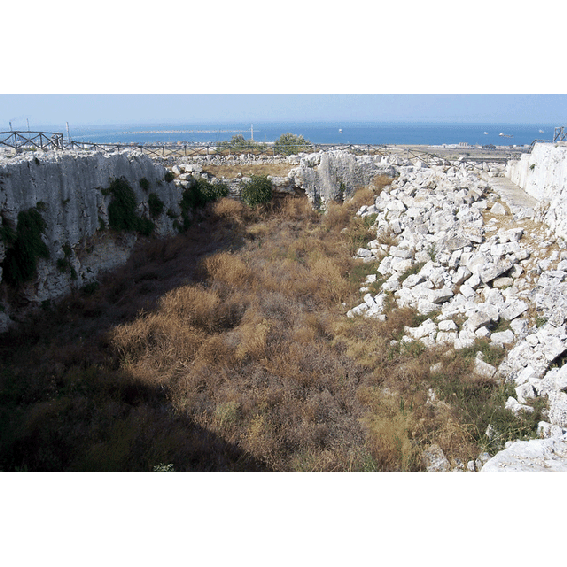

Il secondo fossato (B) si trova alla distanza di circa 86 m dal primo; è lungo circa 50 m, largo 22, profondo 7, e ha forma angolare. Nello spazio tra questo e il successivo si vedono resti di mura appartenenti a un'opera avanzata (C). Il terzo fossato (D), il più lungo (circa 80 m, largo al massimo 15,60, profondo 9) ha anch'esso una forma ad angolo, ma rovesciata rispetto al precedente. Questo fossato è sbarrato a nord da un muro (24; che però è forse di età bizantina) e da un terrapieno, sotto il quale furono trovate monete mamertine, che ne dimostrano l'appartenenza agli ultimi restauri di lerone II.

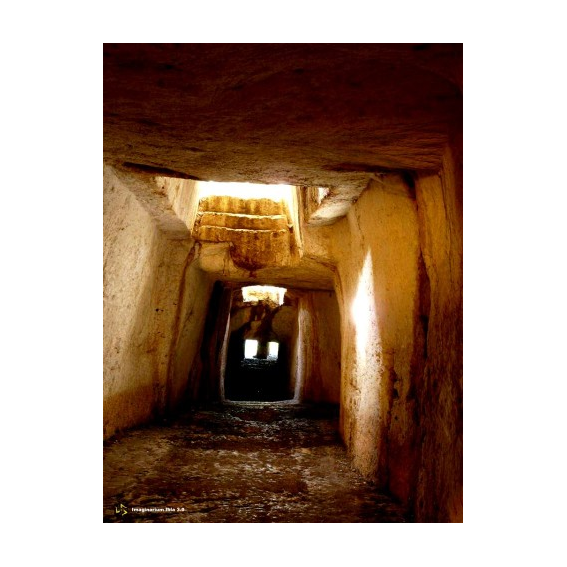

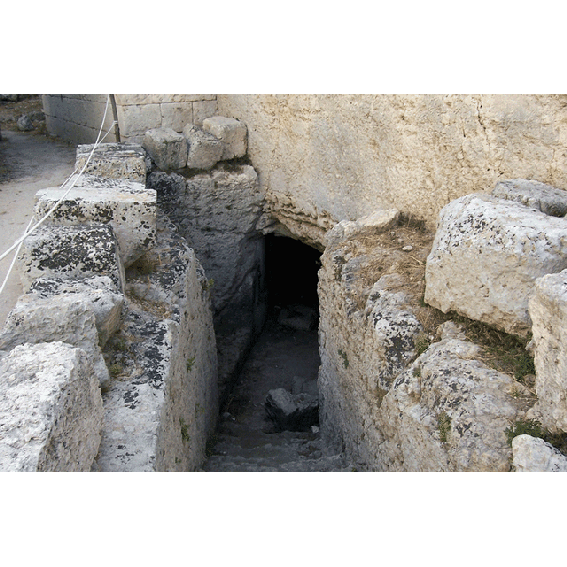

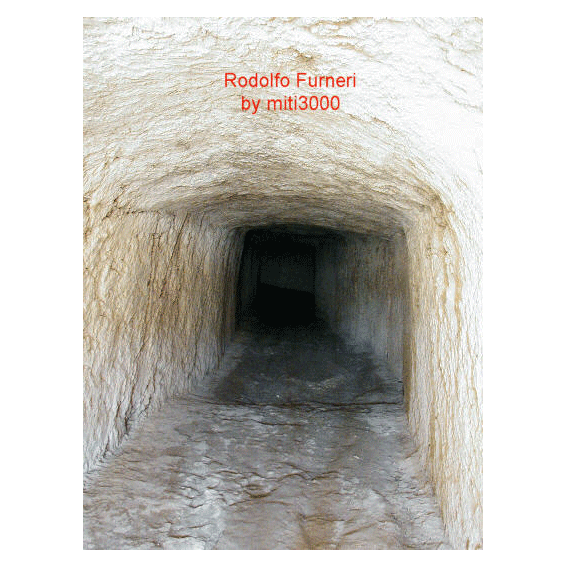

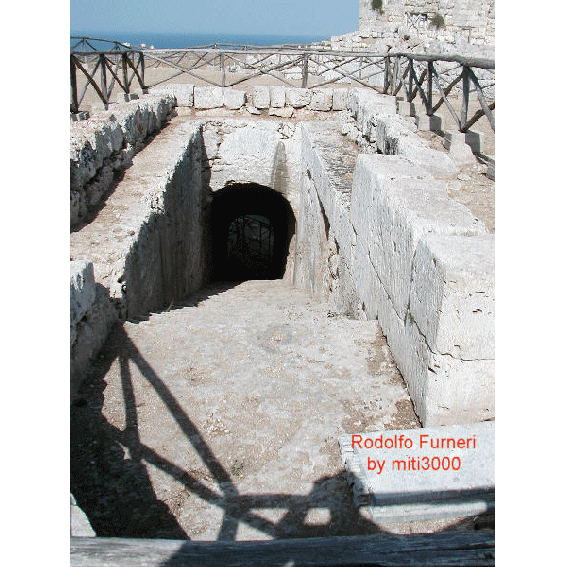

A sud sono tre grandi piloni in opera quadrata (7), destinati a sostenere un ponte levatoio, collegato tramite un corridoio (sotto il. quale sono quattro ambienti: 9) al mastio centrale. Sul lato ovest del fossato sono alcuni ambienti, ai quali si accede da scalinate (5: depositi per provviste?). Sul lato opposto, una serie di aperture con soffitto inclinato verso l'esterno, a visiera, comunica con un lungo corridoio parallelo al fossato, scavato nella roccia (8), collegato da gallerie con il fossato meridionale (9), con la parte avanzata del mastio (10) e con la porta della città (12-13). Questo sistema permetteva di accedere dal terzo fossato pra- ticamente a tutte le altre parti del forte: da qui si poteva colpire, dal basso, chi si fosse affacciato al margine del fossato; ma forse il sistema serviva anche ad asportare, senza esporsi ai tiri nemici, i materiali che fossero stati gettati entro il fossato per colmarlo.

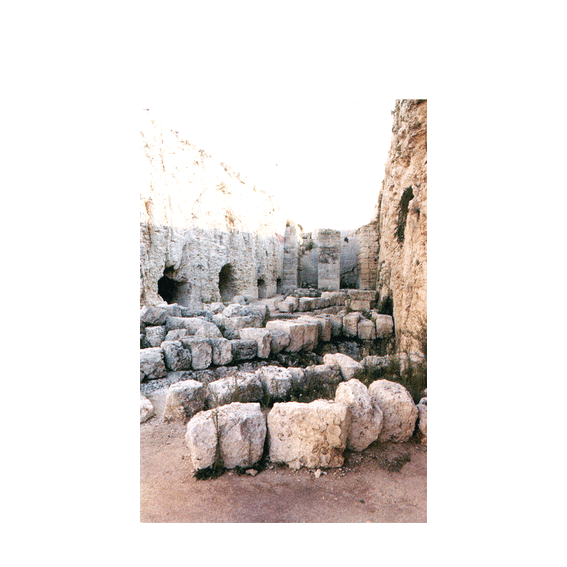

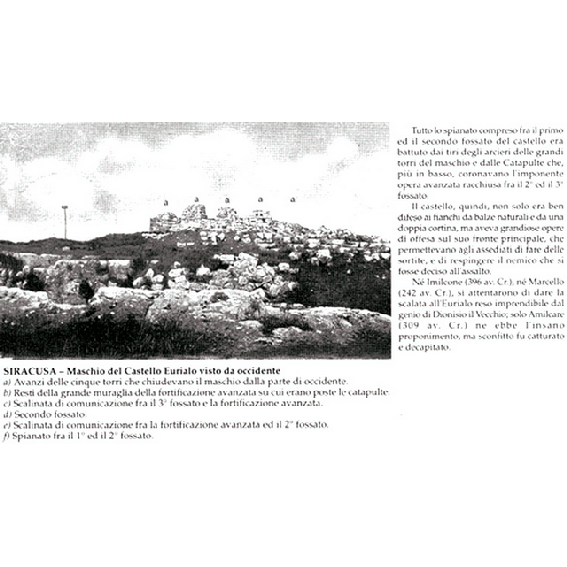

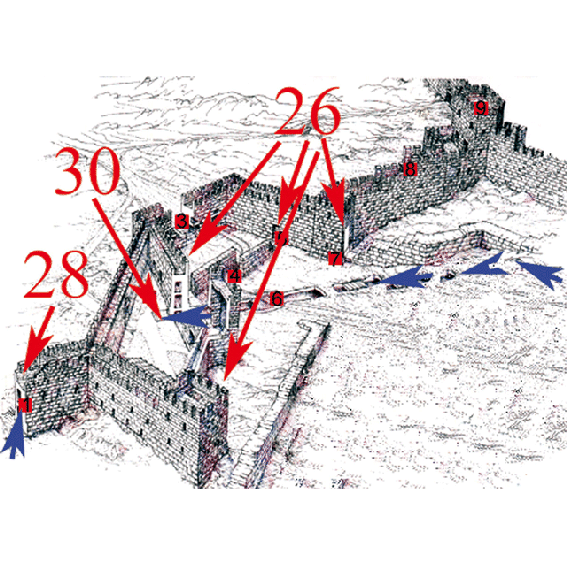

Il mastio centrale era in origine costituito da una fronte a prua triangolare (E), in seguito sostituita dal complesso di cinque torri (29) destinato probabilmente a ospitare le balliste. Sembra che in origine gli spazi tra le torri fossero aperti, e che solo in una fase successiva siano stati chiusi con muri. La parte centrale del forte è costituita dal mastio G, di forma rettangolare irregolare. Qui, e nell'adiacente costruzione trapezoidale K, dovevano essere le caserme (gli ambienti ora visibili sembrano però di età bizantina, come del resto il muro che separa i due settori). Nell'edifìcio trapezoidale erano anche le cisterne (30). Una porta, protetta da una grande torre (16), metteva in comunicazione il mastio con il fossato meridionale (H), che a sua volta comunicava mediante una galleria sotterranea con il terzo fossato (D). All'estremità est dell'edifìcio trapezoidale è una grande torre (25), alla quale si aggancia il tratto meridionale delle mura dionigiane, mentre il tratto settentrionale si innesta alla torre che occupa il vertice nord dello stesso edifìcio (19).

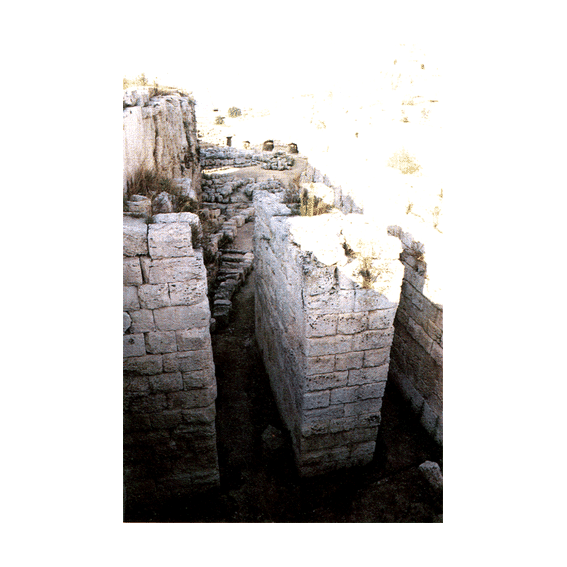

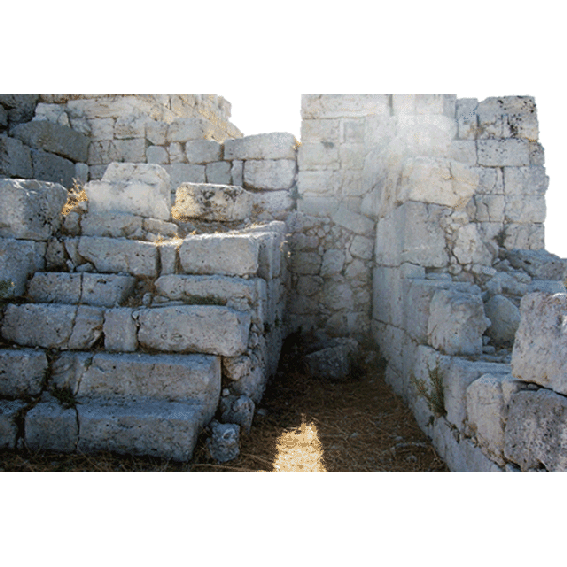

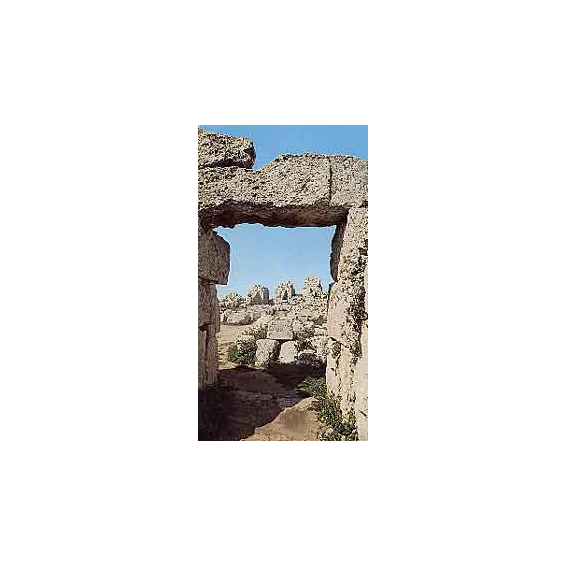

All'inizio di questo tratto settentrionale delle mura si apre una porta (M), situata in fondo a una grande rientranza di pianta trapezoidale, destinata a proteggerne l'accesso (opera a tenaglia). In origine si trattava di un ingresso triplice (tripylon) che fu ben presto ridotto a dipylon, chiudendo la porta centrale (21). Furono allora costruiti due muri sfalsati, che obbligavano la strada di accesso a descrivere una chicane (20). In una fase successiva fu aggiunto un ulteriore grande muro frontale, che nascondeva del tutto la porta alla vista dei nemici.

Entro le mura, che qui raggiungono uno spessore di più di 7 m, sono ricavati camminamenti, che si prolungano anche per un buon tratto del settore nord. A sud della porta è ricavato un forte di pianta trapezoidale (N), difeso da una gigantesca torre, entro il quale doveva . essere collocata una grande catapulta, mo- bile per mezzo di ruote scorrenti entro rotaie, delle quali sono stati scoperti resti evidenti nel corso di recenti scavi. Da questo forte si poteva pervenire, tramite una galleria scavata nella roccia (12-15), all'interno del terzo fossato (D).

Come si comprende, tutto questo complesso sistema di gallerie e di passaggi permetteva ai difensori del castello di spostarsi rapidamente, senza esser visti dall'esterno, da un punto all'altro delle fortificazioni, dove più urgesse il pericolo, e di effettuare sortite alle spalle degli attaccanti.

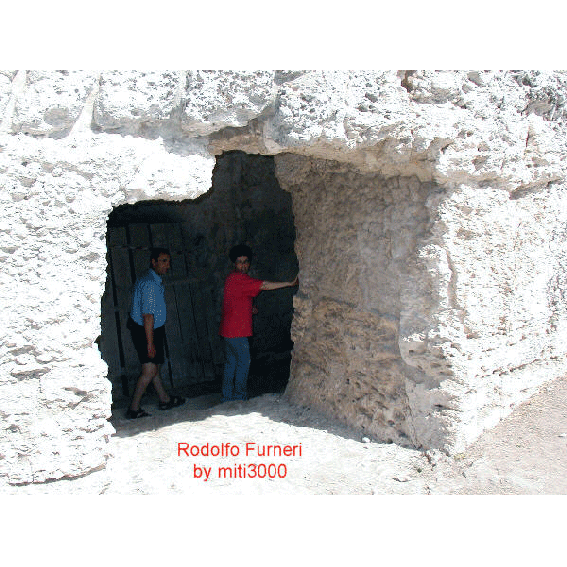

Partendo dal castello si può effettuare la visita del settore nord delle mura, il meglio conservato e il più notevole, anche dal punto di vista panoramico. Molto interessante è il sito di Scala Greca, da identificare con l'antico ingresso della città detto Hexapylon, dove convergevano (e convergono ancora oggi) le strade provenienti dal Nord dell'isola. Qui si notano molte grotte: due di esse (la seconda e la terza a partire dall'uscita della statale Siracusa- Catania) ospitavano un santuario rupestre di Artemide, scavato nel 1900, che ha restituito una ricca serie di terrecotte votive, tra le quali predomina la rappresentazione della dea con il cervo.

Traduzione di Annalisa Giammanco

Eurialo Castle and Dionigi walls

The Athenians siege, demonstrated the vulnerability of Siracusa, in all the north-west sector, where the presence of the wide plateau of Epipole, which dominates the town, made easy the attack from the favourable position and the block of the main street access. Sicilian Diodoro has handed down with many details the initiative about Old Dionigi who, in 401 b.C, when started the campaign against the Carthaginians, wanted to be prepared, beginning the Cyclopes opera to close inside a ring of walls the immense plateau (Diodoro, XIV 18, 2-7). “Having seen that during the war with Athens the town had been blocked by a wall which went from sea to sea, frightening of being, in similar cases, cut out from every communication with the surrounding territory: he knew well, in fact, that the area called Epipole, dominated the town of Siracusa. Applied to their architects, according to their advice he settled to strengthen the Epipole with a wall, up to now preserved around to The Exapylon (the six doors). This place, facing the North, rocky and sheer cliff above the sea, is unaccessible from outside. Wishing that the wall were built quickly, 60.000 best men among the peasants were asked to come from the country, to work for the raising. For each level he appointed an architect, and for each group a master mason, with 200 workers per master. 6000 oxbows of oxes were used in the established place. The activity of so many men, working hard to their aim, represented an extraordinary scene. And Dionigi, to stimulate the enthusiasm of this multitude, promised big prizes to the first finishing the work, especially to the architects, then the master masons, finally to the workers. He himself, with his friends, assisted the works all the day, looking over the place and replacing the tired workers. Briefly, renouncing the dignity of his public charge, he deescalated to a private rank, subduing the hardest work, undergoing the same fatigue of the others, arousing the emulation of the others, who worked even during the night, such was the enthusiasm of all those workers. Thereby the wall was finished, incredibly, in 20 days: it was 30 stadia length, same heights, so thick to be considered impregnable. There were tall towers with low intervals, built with blocks long 4 feet, accurately wedged in”. These works concern only the north part of the Epipole, the most unprotected side, which needed to be thickened, its length, 30 stadia (maybe Attic stadia, about 177,6 m), equivalent to 5528 m. It’s a very precise indication, considering that the length of the Dionigi’s walls in the northern sector, between the sea and the Castle Eurialo, is about 5580 m (Dionigi established a whole number). A confirmation of the description is obtained from the building technique of the wall, completely homogenous in the northern side (clear sign of a unique implementation), whereas huge differences are in the other sectors, realised during longer periods, and by different workmen. The works had to keep on, during the next years, along the southern and eastern sectors, and probably ended in 585, as Diodoro talks of it, mentioning that the walls were finished that year, and that they were the biggest existing in a Greek city (XV 15, 5). The measures were given by Strabone (VI 2, 4); according to him the wall circle measured 180 stadia, that is in Actic stadia, less than 52 km. Even if this is merely a whole number, it’s corresponds with a good approximation to the reality (about 51 km). The southern sector wasn’t still built in 596 results in an event of that year when Imilcione occupied the external area of Acredina (more or less the zone of the Fusco), and plundered the sanctuary of Demetra and Kore. This area, particularly vulnerable, was eventually protected by an enormous fortification, from the “portella” (little gate) of the Fusco southward, including most of the Necropoli.

Near the cemetery, sectors of a wall 6 m width were excavated at the beginning of the last century, but it’s possible that the surrounding wall in this sector was even double. It continued along the border of the terrace of the Fusco, up to connecting with another pieces of wall, on the north of the so called gymnasium, and then with the walls of Acradina.

The most vulnerable point of the Epipole was their occidental vertex, where the big plateau closes up to shape a narrow isthmus, natural point of access of the terrace behind Siracusa. The name of the place, Euryalos, maybe meaning “large nail”, referring to the shape of the isthmus. It’s quoted speaking of the Athenians’ siege: through this point the Athenians entered twice on the Epipole; during the first assault against Siracusa, and then after the re-occupation of the Epipole by the Siracusans, when Demostene tried “to take them back to the enemy” (Tucìdide, VI 97, 2; VI 43, 3). Even Gilippo, come to help the city, entered through the Eurialo; symptom that this was the main access from the inner part of the island (Tucidide, VI 2, 4). The Siracusans were conscious about it, and fortified the access already during the war against Athenians. The first standing fortress was probably built by Dionigi, it took the name of the site. Its dimension were probably remarkable even in the IV century, if during the Cartages siege in 309 the Siracusans could concentrate 3.000 foot soldiers and 400 horsemen (Diodoro, XX 29, 4), who beat off the big army of the enemy, even thanks to the narrowness of the place. Even during the Roman siege Marcello, after occupying the Epipole realized that the castle was impregnable (Livio XXV 25, 2-5) e and he tried to force the overlord of the garrison, Filodemo from Argo, to submit and give the castle. Esichio defines the place as the Acropolis of the Epipole, and Livio speaks about it as a fumulus (isolated hill) or an arx (citadel). Livio himself gives us the best ancient description: “ it’s an isolated hill on the extreme part of the city, in the opposite direction of the sea. It overtops the paths to the inner island, located favourably to receive stocks”.

The remains still visible of the castle only in the least correspond to the previous Dionigi’s construction: they are the results of continuous recreations and improvements, along the period between the end of the V century b.C. and the Roman siege by Marcello. It’s rather probable that the ultimate restructuring (never completed) belongs to the last years of that period: it can be attributed to Ierone II, who, as Plutarch says, made fully use of the technique suggestions of Archimedes (Plutarch, Life of Marcello, 14, 8). It’s probable that the refined installations of the castle, the most complex defensive opera of the Greek world, were projected by Archimedes himself: in fact they correspond to the most advanced step of the Hellenistic technique of construction, which we know through the work of a contemporaneous of the Siracusan scientist, Filone from Byzantium. After a long period of peace, corresponding to the Roman occupation, the castle was re-enabled in the Byzantine period, as shown by some late surviving structures.

The castle (which occupies a surface about 15.000 m2), is anticipated by a little Antiquarium, adapted as the house for the housekeeper, where are conserved the most important materials found during the several excavations, started at the beginning of the last century. There are exhibited: two lion-head drips, from the tower of the central fortification (fortification), dated IV cent. b.C., and then belonging to one of the most ancient phases of the fortification; a relief where it’s represented a catapult (war machine invented by the engineers of Dionigi the Old); fragments from a big Greek inscription, found in front of the door with pincers frame on the north of the castle: it’s read partly the word basileus (<<king>>), and it proves a late intervention, attributed to Agatocle or Ierone II (surely the last), because Agatocle himself was the first dynast assuming the title of king. The structures of the fortress were preceded by three consequent moats. The first of these (A), never concluded, it’s near the Antiquarium, length 6 m and deep 4 m. It has been noticed that it is placed about 566 feet (182 m) from the front of the fortification: it corresponds more or less to the rules of Filone of Bysantium, who affirms that a fortress must be defended by not less than three moats, and that the far one must be located to not less than 535 feet, so that to put the fortress itself out of the sight of the most powerful catapults. The greater distance, in this case, is explained with the fact that the catapults of the castle were located on the tower at a certain height, and consequently their capacity was higher the capacity possible for the offensives, who were lower. The second moat (B) is far 86 m from the first one; it’s about 50 m long, 22 m wide, 7 m deep, and has an angular form. In the space between this and the next it is seen ruins of walls belonging to an advanced opera (C). The third moat (D), the longest (about 80 m, wide almost 15,60 m, deep 9 m ) has also an angular shape, but reversed compared to the previous one. This moat is barred by a wall on the north (24 m; but maybe is from the Byzantine period) and by an embankment, under which were found coins of Mars, which demonstrate belonging to the last restorations by Ierone II.

In the south three big squared piers (7), assigned to sustain a drawbridge, linked to the central fortification through a corridor (under which there are 4 rooms: 9). On the west side of the moat there are some rooms accessing by stairs (5: warehouse for stock food).

On the opposite side, a series of doors with the roof tilted outward, visor shaped, communicates with a long corridor parallel to the moat, excavated in the rock (8), linked through galleries with the southern moat (9), with the advanced part of the fortification (10) and with the door of the city (12-13). This kind of system permitted the access through the third moat towards all the other sides of the fortress: from here they could shoot downward, whoever appeared or peeped from the border of the moat; but maybe the system was also used to take away the materials wasted in the moat to fill it, avoiding to be in the target of the enemies.

The central fortification at the beginning was formed by a triangle prow front (E), then substituted by a complex of five towers (29) set for the catapults. It seems that in origin the spaces between the towers were open, and only in the next phase they were closed with walls. The central part of the fortress is formed by a fortification G, irregular rectangular shaped. Here, and in the adjacent trapezoidal building K, must be the barracks (the rooms now visible seem to be from the Byzantine age, like the walls separating the two sectors). In the trapezoidal building there were also the cisterns (30). A door, protected by a big tower (16), put into communication the fortification with the southern moat (H), communicating through an underground gallery with the third moat (D). At the extreme east side of the trapezoidal building there’s a big tower (25),to which is linked the southern trait of the Dionigi walls, while the northern trait is linked to the tower occupying the north vertex of the same building (19).

At the beginning of this northern trait of the walls there’s a door (M), located in the deep of a big recess with a trapezoidal shape, destined to protect the access (opera a pincers frame). In origin it was an triple access (tripylon), soon reduced to dipylon, closing the central door. So two distorted walls were built, obliging the access road to inscribe a chicane (20). In a next phase another big frontal wall was added, completely hiding the door to the enemies.

Inside the walls, here they reach a thickness about more than 7 m, paths are derived, prolonging following for the most part of the northern sector. On the south of the door is derived a fortress with a trapezoidal plant (N), defended by an enormous tower, inside which must be located a big mobile catapult, thanks to wheels running in rails, of which there have been found evident ruins during recent excavations. From this fortress, through a gallery excavated in the rock (12-15), it was possible to arrive inside the third moat (D).

As it can be understood, all this complex system of galleries and passages permitted to the defences of the castle to move rapidly, without being seen from the outside, from a point to another of the fortifications, where the danger was closer, and to attack the enemies from the back.

Starting from the castle it’s possible to visit it from the northern sector of the walls, the best conserved and the biggest, even for the overview. The site of Scala Greca (Greek stair), could be identified with the ancient entrance of the city called Hexapylon, where converged (and converge nowadays) the streets coming from the North of the island. Here there are lots of caves: two of them (the second and the third starting from the exit of the main road Siracusa-Catania) put up a rock sanctuary of Artemis, excavated in 1900, which gave back a rich series of vow terracotta, between which the predominant is the representation the representation of the goddess with the stag.

DIONISIO I

Nacque a Siracusa nel 432 a.C. da una umilissima famiglia (pare che suo padre facesse il carrettiere); riuscì, giovinetto, ad occupare la carica di scriba. Fu il più accanito accusatore dei generali che, anzicché aiutare gli Agrigentini, li avevano "venduti" ai Cartaginesi.

Astuto e ambizioso, riuscì a farsi accettare dal popolo con incredibili "messe in scena". Fu generale, poi stratego ed infine capo assoluto di ogni cosa. Rafforzò militarmente Siracusa e fortificò Ortigia; si stabilì nell'Arsenale, ritenuto la parte più sicura della città.

Si arricchì facendo confiscare i beni ai più ricchi che, con studiate calunnie, riusciva a fare condannare.

Per dare lustro al suo nome, sposò Aristomaca, figlia di Ermocrate (quasi contemporaneamente sposò anche Doride, una nobile della città di Locri). Appoggiò gli artisti ed ospitò a corte poeti e filosofi. Egli stesso compose delle tragedie giudicate da tutti assai mediocri; a tale proposito si racconta che un giorno abbia fatto leggere un suo lavoro a Filosseno e che questi, trovandolo orrendo, l'abbia strappato senza nascondere una smorfia di disgusto. Dionisio punì l'incauto critico facendolo chiudere nelle latomie. Liberatelo dopo pochi mesi, gli sottopose un nuovo lavoro e Filosseno, senza rispondere, rivolto alle guardie disse: "Soldati, alle Latomie".

Depredò i gioielli dei templi e con trovate teatrali riuscì a farsi consegnare dalle matrone tutti i loro preziosi. Quando sconfisse i Cartaginesi, liberò solo i prigionieri in grado di "regalargli" 300 talenti.

Temendo per la vita, rafforzò la guardia al suo palazzo e non uscì più di casa. Diffidò di tutti, fece crocifiggere il barbiere solo perché "avrebbe potuto tagliargli la gola" e da quel momento si fece radere dalla figlia.

Ad Atene, nel 368 a.C., dopo anni di tentativi non riusciti, ad una sua tragedia, Il riscatto di Ettore, fu assegnato il primo premio. Tale fu la sua felicità che offrì un sontuoso banchetto a tutti gli amici; egli stesso si ingozzò fino a stare male: non si riprese più e morì poco dopo, nel 367 a.C.

Traduzione di Annalisa Giammanco

Dionisio I

He was born to Siracusa in 432 b. C., from a humble family (his father was a cart men); he still young succeeded to have the office of SCRIBA. He was the fierce prosecutor of the generals who, instead of helping the Agrigentians, betrayed them in favour of the Carthaginians. Astute and ambitious, he succeeded to be accepted from the people with incredible tricks and lies. He was general , then strategist and finally absolute head of everything. He strengthened Siracusa and fortified Ortigia; he settled in the Arsenal, considered the safest part of the city. He enriched confiscating the goods to the rich people who, with precise heats, were condemned.

To give prestige to his name, he got married with aristomaca, Emocrate’s daughter (in the same period he also married Doride, a noble from Locri).

He supported artists and invited to his court poets and philosophers. He himself wrote tragedies, judged by everyone, felt offended, and no longer went out from home. He mistrusted everyone, crucified the barber only because “he could cut his throat”, and since then her daughter cut his beard.

In Athens, in 368 b. C., after years of failed attempts, a tragedy of him, Hector’s redemption, received the first prize. He was so happy that offered a sumptuous banquet for their friends; he himself stuffed to be sick; he didn’t recover and died soon after, in 367 b.C.